A Makua in Mbuyuni

By Danielle Chipman

Makua is a word in the Tshivenda language that refers to white people, and I spent three days in a rural South African village called Mbuyuni being primarily identified by this word. It was strange to be in a situation where my race was my defining characteristic. I have been in similar situations during my travels to Ecuador and Guatemala, but I was still struck by a sudden awareness of how being a white person in the United States often lets me ignore my skin color, which is a luxury that many Americans and South Africans don’t have. At no point in Mbuyuni did I feel that I was negatively judged by my race, though; race just seems to be something that South Africans are very accustomed to noticing and discussing. South Africans use race as a descriptor in the same casual way that we would use hair color, height or gender.

While race was the first and most obvious factor that grabbed my attention upon arrival in the village, it was just scratching the surface of cultural differences I would experience during my homestay. I was in Mbuyuni with three other ASU students to conduct surveys about water quality and availability. We were dropped off at the home of a small family with a translator, two jugs of water and three thick paper surveys.

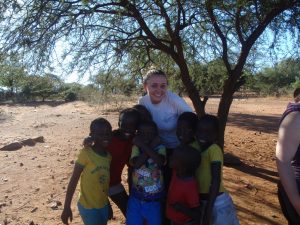

The adults of our host family showed us to our hut, which had a concrete-like dung floor, thatched roof and walls decorated with colorful textiles and old team photographs of the Kaiser Chiefs, and then left us to our own devices. We were almost immediately swarmed by about two dozen village children, who had seen the makuas driving in and were here to investigate. As soon as we emerged from our hut, they all grabbed at our hands and implored us to play. Our translator, Innocent, got some singing and clapping games going, and we ended up playing with the kids for most of the afternoon, even while we were trying to watch a village soccer match. By the end of the day we were sweaty, covered in red dirt and sporting new braided hairstyles, courtesy of the kids. We retreated to our hut to eat what would become a familiar meal of cooked spinach, peanut sauce with mopani worms, and pap, a maize grits-like dish that you ate with your hands.

I was struck by the way we were able to develop fast friendships with these children despite the language barrier. In the past, I have mostly travelled to Latin American countries where I could speak the language. Here, however, I knew only a handful of phrases.

I have always placed great importance on language as a way to communicate with and understand people but this experience taught me that there are other important means of communication. The kids communicated with us through touch and hand gestures, grabbing our hands to pull us around and miming what they wanted us to do. One girl very clearly expressed her boredom to me at one point by frowning, pointing at her face, and raising her eyebrows at me like, “Are you going to come play with us again now?” We all smiled and laughed and played together, and I think that did more to build rapport with each other than any amount of conversation would have.

That’s not to say that language is not important; had I stayed in the village longer, learning the language would have been vital to my ability to participate in village life. We were so completely dependent on Innocent to translate for us that I felt like a child and Innocent was the parent who kept us all in line. Innocent would often have conversations with our host parents that involved a lot of gesturing in our direction, which made me strongly suspect that they were hashing out what exactly to do with these makuas, in the way that responsible adults talk among themselves about how best to keep the kids entertained and out of the way. The language barrier even meant that all of our water surveys were conducted through our translator, which made us ponder what information was being lost in translation, and how our ignorance of the language was impacting our research results. The whole experience made me realize that while I might be a functioning adult in my own community, in Mbuyuni, my inability to directly communicate with people meant that I was completely incapable of being self-sufficient.

Three days quickly passed in a blur of clapping games, pap-eating and cultural confusion. I have no idea what the village kids yelled to us as we drove away from Mbuyuni at the end of our stay, but I know I heard the word makua in their calls. Their smiles and enthusiastic waves suggested that we were parting ways as friends.